“As It Is & As It Was”

Last month, the Society rediscovered a carefully researched and thoughtfully written history of African-American residents of North Reading. It was published in 1968 by local historian Beth Thomson. Recently digitized, the paper is now available on the Society’s website alongside other books and pamphlets on local history. Here are some edited excerpts from the manuscript (entitled “As It Is, and As It Was”):

When the ship "The Susan Ellen" docked in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1635, she probably had completed a trading cycle which introduced and perpetuated slavery in North Reading for the next century and a half. Cargoes of livestock, food, lumber and codfish, collected in Massachusetts and sold in the West Indies, were exchanged for molasses used in the making of rum in nearby Medford.

Rum was exchanged in Africa for black people who were sold as slaves to work the sugar plantations in the West Indies. The gold obtained from the sale of these black people purchased manufactured goods and luxuries in England. The sale of black people in the North American colonies also began. The triangular trade pattern necessitated by the mercantile system of 17th and 18th century England provided the commercial base upon which the Massachusetts colony developed and prospered.

Below: A map showing the Triangular Trade that linked Massachusetts, England, Africa, and the West Indies during the pre-independence period.

A Shared History

“Redding” (present day Wakelfield, Reading, and North Reading)—established in 1651 by a grant from the General Court of Massachusetts—continued within its original borders until 1713. At that time the area now known as North Reading became a separate parish (the North Parish). This means that any discussion of black people in North Reading prior to 1713 is interwoven with the history of those slaves of living in Redding.

Below: North Reading’s First Meeting House (located on the Putnam House grounds). This building served as the North Parish church c. 1717-1752. Parish records suggest that at least one enslaved man (“Old Jonah”) worshipped here during that period.

In 1652, Redding listed 34 white male inhabitants. Twenty slaves—14 male and 6 female—are accounted for in 1655. Assuming that each white male headed a household and that the town grew by no more than four households between 1652 and 1655, it is likely that every other household possessed a slave.

The first black people sold in the Massachusetts colony were servants for life. They were forbidden to marry whites, unable to continue their African cultural traditions, and scattered geographically irrespective of the location of their kin. In North Reading, it is said that the old Jeremiah Swain home on Elm Street housed a 30 foot-long wooden log in the attic where slaves were chained until they could be sold. Deprived of their own culture, black people were excluded from the colony’s white-dominated society.

In 17th century Massachusetts, black people were generally not listed in the church rolls. Later, that changed. By the 1730s, North Reading parish records show that “Old Jonah,” a slave owned by Jonathan Flint, attended the church. Yet black people like Jonah were not able to participate in local decision making because their servitude was perpetuated by laws which denied them the right to hold property. To participate in Redding town meeting, a man had to have "an estate of freehold in hand of 40 shillings per annum or other estate to the value of 40 pounds."

Below: A c. 1730 entry by the Reverend Daniel Putnam—minister of the North Parish church—in his parish book referring to Jonah (alias Ceasar), a slave owned by local farmer Jonathan Flint (NRH&AS Collection).

In 18th century Redding, slaves provided labor in the homes, farms, and businesses. An expenditure document from 1750 records that the "First Parish (Wakefield) paid Mr. Hobby for his negro's sweeping the parish house and ringing the bell for one year: three pounds, ten shillings.” Another document records the story of Old Doss,"a negro of Samsonian strength” who helped build the foundation of the First Parish Meeting House by lifting heavy granite blocks into place.

Documents show that some slave owners treated their human chattel more humanely than others. In his 1662 will, First Parish minister Samuel Haugh asks that his wife Sarah should take care of "my two negroes, Frank and Mary (if they survive me)” and that “besides what I have given to Frank and Mary, I do give them a cow.” Likewise, a headstone (pictured below) in N. Reading’s Park Street cemetery pays tribute to local farmer Timothy Russell’s black manservant: “In memory of Prince Russell, a member of [the Russell family], who died July 1795 in the 25th year of his age.”

Despite such examples of compassion, black people living in colonial Redding were generally treated poorly. For example, the separation of black women and children from black men occurred when financial profit was desired. In 1753, documents record that “Thomas Nichols of Reading sold to Phineas Sprague, of Malden, a negro woman, Peggy, and a negro boy, for the sum of 35 pounds, 6 shillings, and 8 pence.” Designed to encourage the return of runaway slaves, a system of bounties also operated locally. Documents record how, in 1723, Redding slave owner Benjamin Poole advertised for the “return of a negro man” who had run away from him.

Wars of Independence

For black people living in colonial Redding, the wars of the late 18th century presented opportunities to gain their freedom. During the French and Indian wars from (1692 to 1760), local black men were able to buy their freedom by going off to fight. fought andbought their freedom. One such slave was a man named Mingo (owned by Jeremiah Swain of North Reading) who served in a provincial militia unit under Captain Jonathan Eaton, likely in Nova Scotia. No account of his mustering out has been found, but he would have been freed upon leaving military service.

When the Revolutionary War began, 20 to 30 people of color reportedly lived within the boundaries of North Reading, Reading, and Wakefield. Their recorded legal names—Peter Freeman, Cato Freeman, Sampson Blackman, Primus Blackman, among others—suggest a way of life very different from white townspeople. Unfortunately, there are no records that tell us which of these black men gained their freedom by agreeing to serve in the Continental Army.

Below: American soldiers at the siege of Yorktown—including a black soldier from the 1st Rhode Island Regiment (Jean-Baptiste-Antoine DeVerger, watercolor, 1781).

In North Reading, black men willing to serve in the Continental Army were set free upon enlistment and the Parish residents pooled resources to compensate their masters for the loss of their slaves. In the 1784 town warrant, those present were asked "to see if the [North] Parish will allow anything to Thomas Taylor for Luke Richard serving in the army for the year 1776." Even retroactive compensation was not uncommon. In the 1788 town warrant, “Capt. Jonah Nutting asked for a bounty for his [black] servant going into public service in 1776."

Military service was not the only path to freedom, however. Some slaves struck agreements with their masters. One such agreement—certified in April 1776—reads: "Whereas, I [Samuel Bancroft], the subscriber, have a negro man named Cato, who hath requested that he may, in some future time, be made free, I hereby declare it my purpose and design, that if said Cato continue an obedient and faithful servant for the space of three years next after the date hereof, that at the end of said term of three years, said Cato shall be set free."

Some freed black men, meanwhile, bought their relatives out of slavery. For example, records show that "Old Jonah" [mentioned above] "received his freedom by purchase from his son, Peter," who served and died in the Revolutionary War. In 1783, a few years after the end of the Revolutionary War, the new state of Massachusetts ended slavery in the Commonwealth.

No longer bound by slavery or indentured servitude, most black families chose to leave Redding in search of economic opportunities elsewhere. The exception was Pomp Putomia—a former slave of Noah Eaton—who acquired property locally and is remembered as a philanthropist who was "intelligent, modest, unassuming and highly respectable." His son Amos, suffered severe financial losses after investing in the the unprofitable Andover Turnpike (modern day Route 28); no record of his heirs has been found. Surviving records suggest that North Reading had very few black residents in the two centuries following independence.

According to hearsay, some residents of North Reading participated in the abolitionist cause at least to the extent of providing shelter to those fleeing slave states via the Underground Railroad. The old Town Farm (207 Park Street) is said to have space behind the chimney where runaway slaves hid; the Fred Child estate (unlocated) and a since-demolished home located on the site of the Eisenhaure Farm (1 Oscars Way) are also mentioned. However, because the Underground Railroad was an illegal activity, documentation is difficult to find.

As It Was… (in 1968)

The following paragraphs come from the first section of the 1968 report, which details findings from the author’s research interviews with African-American families living in North Reading at that historic moment in U.S. race relations:

In North Reading, black people have met with difficulty in finding housing and financing those houses made available to them. Varying degrees of difficulty were reported. Some encountered none; others required assistance from outside agencies in order to locate homes here. At least one black couple, both professional people and friends of professional people in the community, were refused residences in the town by a local realtor. Another incident concerned an educated middle-class black family who chose to move to another town. A series of neighborhood indignities and harassments were cited as reasons.

Individual black people in North Reading have experienced discrimination in community services offered freely to white individuals. Instances exist where checks were not cashed by local grocery stores when ample identification was provided. The parents of the fifteen black children in our community unanimously praised the school system and the education their children received.

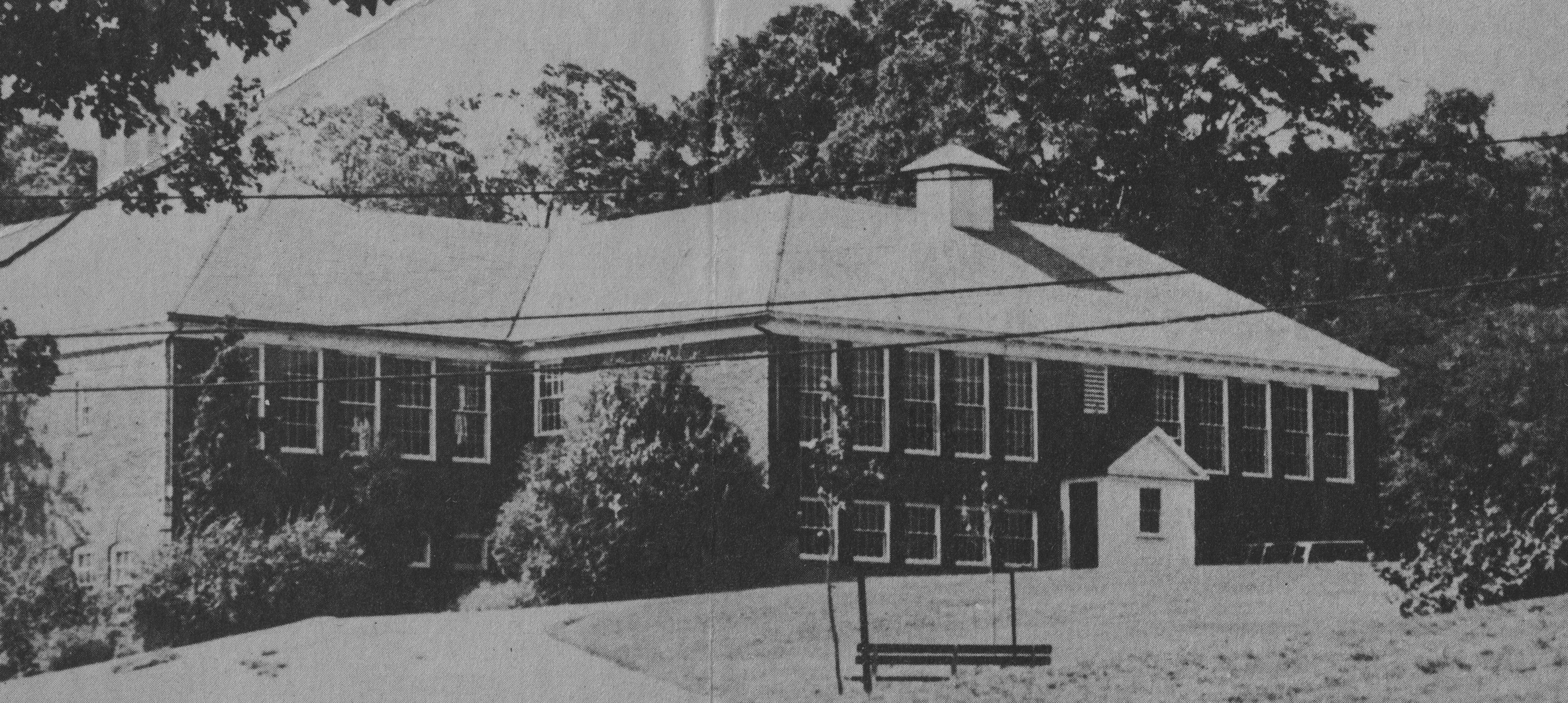

Below: A picture of the Batchelder School taken in 1971, three years after the research interviews for As It Is, As It Was were conducted. In those interviews, African-American residents of North Reading held positive views of the school system (North Reading Transcript).

The neighborhood response to individual black families has been varied. Reports have been received of adults being "disagreeable with black children," of initial unfriendliness of nearby residents, and of "being stared at" in local stores. An instance where a family received sufficient harassment to force them to move out of town is noted above. However, some instances of neighborly concern were described; for example, help during times of sickness.

Are you a person of color living in North Reading? The North Reading Historical & Antiquarian Society would like to hear from you. As part of our oral history program, we are collecting stories of North Reading past and present. Collecting stories and items relating to current history is part of the mission of every historical society. If you would like to talk to us, reach out to: info@nreadinghistory.org.